The UPA has made financial inclusion a major plank of its socio-economic programmes. Research by SKOCH Group on the state of financial inclusion in the country shows that most efforts have been stillborn. What went wrong and how can we chart a new way forward, asks TEAM INCLUSION

In the 1980s famous BBC serial Yes Minister, the minister’s permanent secretary declares, when questioned on the wisdom of the bureaucracy on setting spending priorities: “The public doesn’t know anything about wasting government money. We are the experts.”

The minister sets the policy, and the bureaucracy bungles it. Maybe, that happens everywhere, and in India, this seems to be the operating principle of governance.

If there is one area where the political and economic vision and commitment of the UPA government is well articulated, it is financial inclusion. However, a closer look will reveal that the bureaucracy and the regulator have been at it, botching up the plan through indifference and unwarranted policy interventions.

On 1st January 2013, the UPA-II government launched its ambitious scheme of direct cash transfer of subsidies. It was, however, a watered-down version that was rolled out. Originally to be introduced in 51 districts, the government curtailed the number of beneficiary districts to 20 at the last minute. It covers only seven welfare schemes instead of the 20 initially planned. Food, fertilisers and fuel have been kept out of its purview currently. The government also renamed the scheme as direct beneficiary transfer (DBT), ostensibly to avoid the controversy of doling out cash for votes.

Such caution is warranted as the DBT scheme is likely to attract adverse attention from the strong lobby of pro-poverty politicians and the NGO industry simply because it makes good economic sense and has amongst its supporters not just economists but also a large number of the middle class that has increasingly become frustrated with their tax money being wasted through a very leaky delivery system and subsidies that are too broad based and cover a lot more people than just the poor. No wonder that Rahul Gandhi has conceptualised this scheme as his trump card for 2014.

There is a telling gap between ambition and reality, even though Finance Minister P Chidambaram calls DBT a ‘gamechanger’ and Congress party managers believe the scheme will help the ruling alliance win yet another mandate in the general elections of 2014. The cash subsidy benefit will go directly into the bank accounts of beneficiaries who meet the mandatory requirement of having an Aadhaar card. The government says the programme can generate much-needed budget savings by eliminating corruption. It may not cut down the bloated subsidy bill of Rs 1,640 billion, but officials hope it will ensure benefits reach targeted groups and prevent leakages.

A deeper look reveals that the programme suffers from several inconsistencies that will inevitably make the whole idea of direct cash transfers ‘doubtful cash transfers’ at best, or ‘derailed cash transfers’ at worst. The infrastructure that will facilitate the smooth functioning of DBT simply doesn’t exist in rural India. The pilot programme in 51 districts was predicated on the supposition that all these districts are 100 per cent (or even 80 per cent) financially included; this is simply not true. SKOCH recently conducted a workshop and the consensus amongst senior bankers there was that a fairly inadequate number of people in these districts have got bank accounts. Even the bank accounts that exist, quite a few are not linked to the Aadhaar number. Similar is the case with the social schemes as their beneficiary databases too are not linked to the Aadhaar system. So the question is, who will get this money and how?

One solution that has come forth with the intervention of Jairam Ramesh, Minister for Rural Development, is to use post offices for disbursement of DBT. But he recognises the fact they are not ready. His ministry, in fact, has had first hand experience of MGNREGS, where in there has been a mass migration of benefit transfer from post offices to banks. Quite a few states have found shifting to a manual system better. The post offices simply do not have the infrastructure, technology or competent manpower to be able to handle bank functions and their own transformational project called Project Arrow has become a case study in botching up projects of national significance. The reach of the post office system is unquestionable therefore, in order for DBTs to be routed through this system, it will require a lot of catching up.

DBT is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Only some subsidies are amenable to DBT (e.g., pensions, MGNREGS wages, etc.) while others (food, education, health, etc.) require a more cautious approach. There is talk of a 3 per cent transaction fee for disbursements in pilot districts (but, what about deposits?) and shared ATMs for all banks being provided by third party service providers in a state. The moot question is: Is this practical?

Fortunately with a very significant political focus on this scheme it is quite likely that all these issues would be sorted out more sooner than later and given the resolve of the government to get it going, banks, institutions and domain ministries will fall in line. This hopefully will address the major issue of providing bank accounts to the unbanked before the 2014 elections.

DBT cannot be a substitute for good governance and systemic reforms at the grassroots level. It is not a silver bullet to achieve financial inclusion, either. This is essentially because all the woolly talk about welfare collides with ground reality. Programmes aimed at achieving financial inclusion have proved to be sterile so far in the country. “Government activism continues to be absolutely essential, but it needs to be re-targeted toward health and education facilities, and infrastructure in public services. This will also increase the possibilities of higher earnings. Inclusion is not about redistribution but creating additional opportunities,” says Ashima Goyal, Professor of Economics at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research (IGIDR).

“Access to finance by the poor and vulnerable groups is a pre-requisite for poverty reduction and social cohesion. This has to become an integral part of our efforts to promote inclusive growth.” Thus begins the recommendations of the Committee on Financial Inclusion chaired by C Rangarajan, released in February 2008. The recommendations outlined the various financial services that would be needed to underpin inclusive growth such as credit, savings, insurance and payments, and remittance facilities. The objective of financial inclusion is to extend the scope of activities of the organised financial system to include within its ambit people with low incomes, the committee declared.

The UPA, since 2005, has made financial inclusion a major plank of its socio-economic programmes. The term ‘financial inclusion’ began gaining currency after Finance Minister P Chidambaram used it in his Union Budget 2007-08 speech, defining it as “the process of ensuring access to timely and adequate credit and financial services by vulnerable groups at an affordable cost”. In the speech, the finance minister announced the government’s resolve to implement two decisions of the Committee on Financial Inclusion. The first was the institution of a Financial Inclusion Fund (FIF) to meet the cost of developmental and promotional interventions. The second was to establish a Financial Inclusion Technology Fund (FITF) to meet the costs of technology adoption.

The Union government’s plan, since Mission Financial Inclusion was rolled out in the 2000s, is pivoted on leveraging the latest biometric identification techniques and mobile phone technologies to make the effort widespread and sustainable. Since that landmark speech, several panels have been formed to get to the bottom of the concept and come up with fresh ideas on how to make financial inclusion the holy grail. As recently as last October, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) had named a panel whose mission is to give the objective a whole new direction.

In an article in this edition of the magazine, Rangarajan again defines financial inclusion as a three-way process. One, as making available, particularly credit services, to the vulnerable sections of society. Second, making available financial services to all activities within the country, i.e., whether it is agriculture or small-scale or industry or services. And third, a more balanced regional development in the sense that regional disparities in the availability of financial services must be eliminated.

Yet, the report card so far reads dismal. The heart of the matter is that applying biometric identification techniques and mobile phone technologies can only be effective when implementation is flawless. However, the implementation part has been turned into a tangled web of bureaucratic indifference, misguided policy interventions and a less than assertive regulator. This continues to scupper good intentions and makes schemes like DBT leaky and ineffective.

Montek Singh Ahluwalia, Deputy Chairman, Planning Commission, has no illusions about where we have reached on financial inclusion. “Both the 11th as well as the 12th Five Year Plans stressed inclusive growth. One of the main pillars of inclusive growth is financial inclusion, especially because empirical evidence seems to suggest that reforms over the last twenty years or so have led to inequalities in the economy. Unfortunately, financial inclusion has not got the attention that it deserves,” he says.

The SKOCH Group has been researching inclusion since 1997. Its research, over the years and particularly since it proposed a model of inclusive growth in 2009, shows that financial inclusion has become a ‘populist’ term that has lost meaning under the weight of bureaucracy and half-baked – or even half-hearted – implementation.

India has the dubious distinction of having the largest unbanked population in the world. According to authentic estimates, 65 per cent of the adult population in India is excluded from the formal financial system. Since 2004, the RBI has worked in tandem with formal banking institutions to open almost 100 million so-called no-frill accounts. These accounts, the RBI stipulated, were to target the poorer and weaker sections of society.

Montek doesn’t hide his frustration about the nation’s failure in spreading the banking network. “According to the 2011 Census there were over a 100 million households, out of the total 247 million households in the country which did not have a bank account and even those that did get an account (in fact in the last year-and-half a very large number of them have been covered in terms of the no-frill account), does this really amount to financial inclusion? The answer would obviously be no,” he says.

This is of course damning indictment from a high-ranking government official. However, it is interesting to note that ‘underbanking’ tells only a portion of the whole story. There is a darker truth: of how the plan to make banking a vital component of financial inclusion has failed.

“Transaction cost or cost of delivering small amounts of credit is very high. Several measures have been tried – group lending, lending through micro-credit institutions, business correspondents – all with an effort to reduce cost of delivering credit,” observes noted economist, Nitin Desai. Still, financial inclusion remains a far cry, he adds.

SKOCH has done extensive research on the subject. About eight years into the RBI’s strictures on no-frill accounts as an instrument to make India’s growth inclusive, the central bank’s own data finds that between 2004 and 2012, the change in percentage (46 per cent) of total bank branches reflects the yawning gap between urban/semi-urban and rural India in terms of penetration of banking services. In the same period, the percentage of growth of new bank branches in metro cities went up by 93.63 per cent, urban areas by 72.12 per cent and 69.61 per cent in semi-urban areas. In contrast, new bank branches in rural areas – India’s poverty-stricken heartlands – registered a measly 12 per cent growth.

What does that tell? “During 1990-2010 the number of rural branches opened was less than the number of urban, semi-urban and metropolitan branches. There were no specific guidelines for rural or urban areas. That is why we said 25 per cent of all branches should be opened in rural areas,” says K C Chakrabarty, Deputy Governor, RBI.

Moreover, RBI data reveals that population per bank branch office declined from 16,000 in March 2004 to 13,000 in March 2012. Yet, given the under-par growth rate of rural bank branches, the decline in population under banking cover is more pertinent to urban or semi-urban areas than their rural counterpart.

The RBI, when it introduced the business correspondent (BC) model in January 2006, hoped that this method will take formal banking services to rural India. The model was touted as the panacea for providing hassle-free banking services to the poor and was implemented with vigour. For instance, in her speech in February 2011at the launch of the Swabhimaan programme, UPA Chairperson Sonia Gandhi declared that the BC model will ensure banking facilities in habitations with a population of over 2,000 by March 2012.

BCs were supposed to make banking accessible to even the remotest areas of the country. They work on a commission basis and are paid by the bank. They are barred from charging any money from the customers. RBI guidelines listed disparate entities, including non-governmental organisations and microfinance institutions registered under the Societies Act or Indian Trusts Act, societies registered under the Mutually Aided Cooperative Societies Act or the Cooperative Societies Act of states, post offices or various other individuals, who qualify the RBI criteria eligible for becoming a BC. The model was founded on the thesis that these agencies or individuals are appointed by banks to act as their agents and provide basic banking services such as opening bank accounts, accepting deposits and disbursing money.

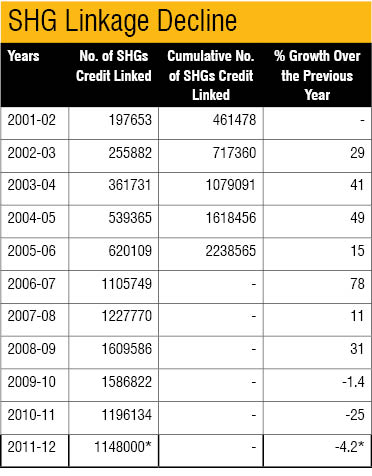

Yet, the results have been patchy. In the words of Chakrabarty, “Earlier, to start banking operations, a banking license was required. But today anyone can be appointed a BC with a handheld device and a mobile phone who can go anywhere to do a banking transaction. In the process, more than 100,000 BCs have been employed, but they are not delivering desired results.” The reality is that the entire priority sector developmental banking responsibility had been palmed off to BCs, who are in any case not working very well “The number of individual business correspondents or facilitators has not increased even though the Reserve Bank has expanded the category of people who can become business correspondents and facilitators. We really need to introspect,” says Rangarajan. “One of the things that can help the organised banking system is to bring more and more people into the purview of the organised financial system is the SHG–bank linkage model. Business facilitators and business correspondents do have a role to play in outreach,” he added.

Since its introduction the BC model has struggled to create a viable business model and hence generating volumes has been a big hurdle. To compound their woes, most BCs are confined to no-frill accounts and limited remittance services, thus encumbering their product and service range. In states where the BC model is up and running, like Maharashtra, Bihar and Jharkhand, the experience shows that it has run out of steam owing to flawed cost structure, lack of commitment on the part of banks, absence of financial literacy, lack of knowledge between customer service point operators (CSPs) of BCs and clients, and the near-absence of a robust grievance redressal system.

In 2009, there were 13,000 CSPs and the number went up to around 116,000 in March 2012. Out of these, 72,000 were added under the financial inclusion plan of the Union finance ministry. These cumulative numbers are, however, deceiving because in the last two years, many CSPs have closed down but are still reflected in the cumulative numbers. It’s interesting that when SKOCH did field research, it found that even out of the 72,000 that have reportedly been set up under the financial inclusion plan, many were missing and some others were operational only partially. So while these CSPs on paper, the data is incorrect by almost 30 to 40 per cent.

“BCs have been appointed in many villages, but they have not been able to come up to the expectations of the bank in that area of reaching out to customers. There is a learning curve. Not that we have not made efforts, but we find that the cost has been a barrier in scaling up. It may take us a while to revise our business models to make it more cost-efficient,” observes B A Prabhakar, CMD, Andhra Bank.

“We offer smart cards with basic built-in overdraft facility and our BCs are trained to extend this business for procuring applications for KCCs (Kisan Credit Cards) and GCCs (General Credit Cards). BCs get an incentive for each completed transaction. Despite all this, it is not scaling. Probably, we are not addressing the demand properly leading to productive money going towards consumption,” says M V Tanksale, CMD, Central Bank of India.

Analysis of the BC model also shows the urban-rural divide. The average growth of urban CSPs has been around 400 per cent in 2011-12, whereas rural CSPs grew by merely 81 per cent.

Focus on opening no-frill accounts has led to neglecting other banking products like fixed deposits or recurring deposits. Nevertheless, the number of active accounts reported by different banks varies between 3 per cent and 20 per cent. But the national average is only 11per cent, according to SKOCH research. Also, just under 2 per cent of the total no-frill accounts (138.50 million accounts by March 2012, according to RBI data) have an overdraft, which totals a mere Rs 1.08 billion. (Refer Table II)

Financial illiteracy, low income savings and lack of bank branches in rural areas continue to be roadblocks to financial inclusion in many states

As of the case in 2009 when SKOCH had come up with the first state of the sector report, the usage of no-frill accounts was a minuscule 11 per cent. The whole objective of opening these accounts was to give some semblance of credit, only 2 per cent of these accounts actually have an overdraft account facility. The Indian Banks’ Association spent Rs 1 billion on advertising the fact that they had no-frill accounts out of which Rs 10.08 million had been given overdrafts. They should have airdropped that money to the poor. Similarly, about Rs 60-70 billion worth of technology has been procured in the name of the poor and the end result is that only 11 per cent of non-frill accounts are in actual use.

This leads to three obvious conclusions. One, the total figure of no-frill accounts is nothing but misleading. Second, there are only a trivial number of Kisan Credit Card and General Credit Card accounts that are linked to no-frill accounts. And third, no-frill accounts will remain active only if there is an overdraft incentive attached to them.

All in all, there is precious little instrumentality available to give credit in these accounts and it is an alarming fact. It is very clear that a big chunk of the no-frill, low-income accounts either exist only on paper (the system of weeding out dead accounts in our banking institutions leaves much to be desired) or have sub-optimal use. They offer, in other words, no crutch to the financial inclusion goals of the government. “No-frill accounts really amount to statistical inclusion because a very large number of these no-frill accounts (more than 80 per cent) are inoperative. This is also amply demonstrated by the fact that even though RBI suggested that overdraft facilities be given liberally to these accounts, only about 1.5 per cent of such accounts have enjoyed this facility,” Montek observes.

With such a big mismatch between ambition and success, how can the challenge of enabling small and marginal farmers obtain credit at lower rates from banks and other financial institutions, a goal enunciated in the Swabhimaan campaign be met? However, financial illiteracy, and low income savings and lack of bank branches in rural areas continue to be roadblocks to financial inclusion in many states.

“We need financial literacy and skill development. We are lending to people who do not have adequate skills to utilise money skillfully,” remarks Tanksale.

Skoch also focused its research on priority sector lending. Table II shows that priority lending decelerated to 12.9 per cent during 2011-12 from 13.5 per cent in the previous year. Non-food credit growth was down to 17 per cent in 2011-12 from 20.6 per cent in 2010-11. Another alarming fact is that cooperative societies, a backbone of the rural economy, are dying a slow death. Data for 2010-11 shows that total demand for medium term and other loans issued as well as total collections were at an all-time low. (Refer Table III)

Domestic credit provided by the banking sector in India stands at an abysmally low level compared with many emerging Asian economies. There is a strong need to develop stronger linkages with the real sector in this respect. “The approach paper to the 12th Five Year Plan did recognise the need for the banking sector to expand and for microfinance to be revitalised for fixed capital formation to grow at a rate consistent with the GDP growth of 9 per cent. Unfortunately, the policies to make this happen are missing,” Montek opines.

S S Tarapore, Distinguished Fellow, SKOCH Development Foundation, has another take on financial inclusion. “You must have a viable delivery mechanism. Postal system has the widest geographical coverage. Commercial banks are nowhere near it and any amount of attempted financial inclusion wit

It is felt that the IBC or the Insolvency Bankruptcy Code has been a game-changer in economic legislation. Five years into its introduction, the IBC is a well-oiled apparatus, with...

The discourse around cryptocurrency, particularly in India has been clouded by heavy advertising and promises of getting rich quickly. However, there is a need to center this discussion by highlighting...

The Indian economy has come a long way since the 1991 economic reforms, it has been the fastest-growing major economy in the world for a large part of the previous...

Sharing his views on 'Strengthening Federalism' at SKOCH India Economic Forum N K Singh, Chairman 15th Finance Commission today emphasized on the need for constitutional reform, revisiting of centrally sponsored...

Pradhan Mantri MUDRA Yojana (PMMY), which provides access to institutional finance (MUDRA Loans of

"American roads are good not because America..

State Rankings Highlights -: Odisha scaled to number..

In the run-up to the elections, the most..

Step 1: Call for Project Submission Call for..

Inclusion is the first magazine dedicated to exploring issues at the intersection of development agendas and digital, financial and social inclusion. The magazine makes complex policy analyses accessible for a diverse audience of policymakers, administrators, civil society and academicians. Grassroots-focused, outcome-oriented analysis is the cornerstone of the work done at Inclusion.